In the early 1900s, working as a Pullman Porter was one of the few stable jobs available to Black men following the Civil War. Employed by the Pullman Company to staff its sleeping cars, porters faced severe exploitation, enduring long hours, low wages, and racism. They worked grueling 16-hour shifts, relying on tips to supplement their inadequate pay, all while maintaining a subservient attitude toward passengers. Despite these harsh conditions, porters held onto their dignity and pride, but they needed a leader to organize their efforts for change.

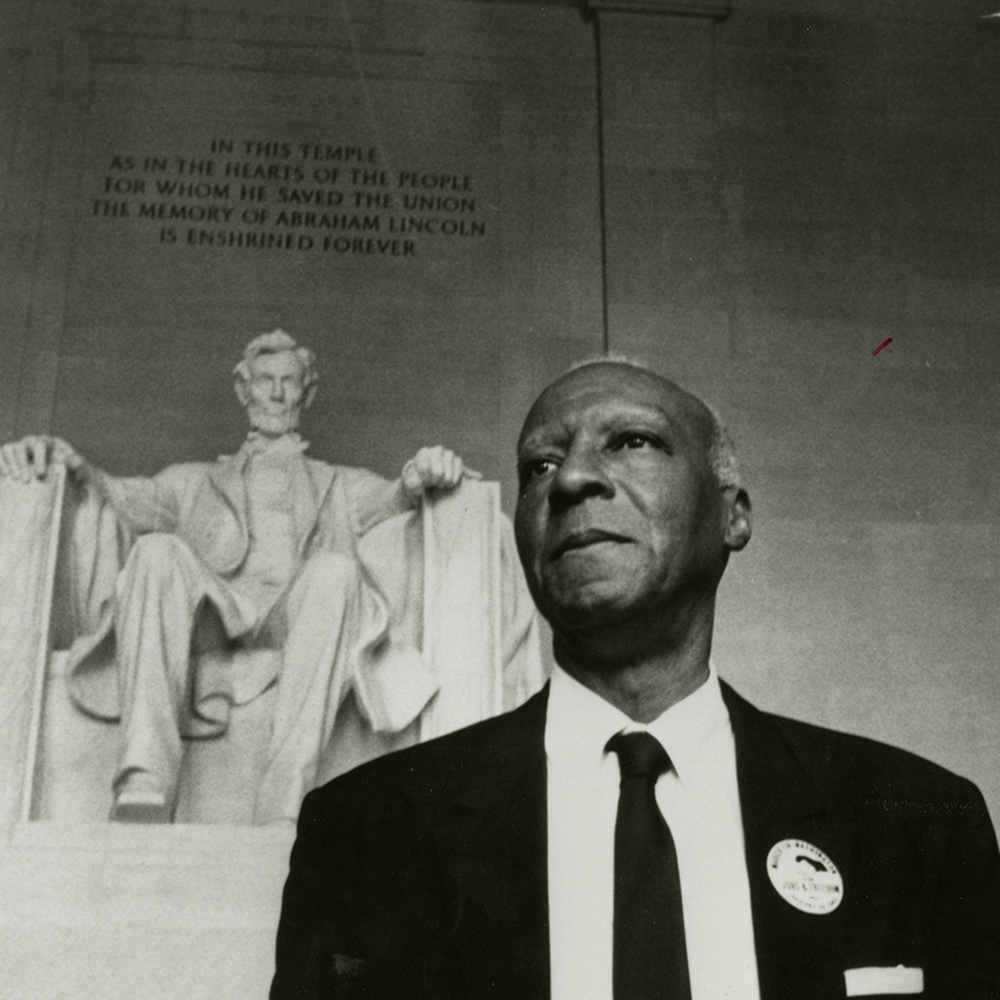

That leader was A. Philip Randolph, a vocal activist and editor of the socialist magazine The Messenger. In 1925, Randolph helped form the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), creating a pivotal moment for Black labor. The Pullman Company fiercely resisted, using tactics like intimidation, spying, and firing union supporters, but under Randolph’s leadership, the porters remained steadfast. After more than a decade of organizing and legal battles, the BSCP won a collective bargaining agreement in 1937, becoming the first African American union to do so with a major corporation. This victory secured better wages, improved working conditions, and a sense of respect and dignity for Black workers.